What is a Background?

Is your history worth knowing?

Friar Tuck, Rhead Louis, Bold Robin Hood and his outlaw band, oldbookillustrations.com

This is, of course, a question for your character, not so much you, as the player. The background of a character has long been something I have taken great joy in fleshing out. When 5e came out with its list, their descriptions, and their tables of traits, flaws, ideals, and bonds, I was hooked.

Over time I have often looked to other games and systems for ideas on how to expand this system. I have heard of Traveler, and the legendary character history “mini-game” in which your character can die before they ever get off the ground, and I loved it. Having never had the opportunity to play Traveler, yet, I sought out a digital copy and tried to decipher how it worked and if it could be ported into something like 5e, or at least medieval fantasy games.

Why expand backgrounds?

This is one of those questions I have learned to ask after all of my years of tinkering. The current system works, and unfortunately, a lot of that system isn’t even applied. Most of the other players I see don’t even touch the character traits section of their background, instead looking to the proficiencies granted and the unique feature, looking to make their “build” better rather than fleshing out a character.

So if what’s there isn’t being used, why expand it? This question leads us to the next important question: what is this game about? When it comes to my Heartbreaker, the game is about more than “builds.” Heartbreaker is about longform play with defined characters. The characters are defined because the challenges they will face are more than monsters and hazards, they are the very people that make up the society around them.

Monsters and the wilderness test the characters in ways that the system already accounts for. In order to test a character against a powerful ruler or nefarious guild, the character must know what they value and which lines they are unwilling to cross. If the monarch is able to usurp the laws, because they are the laws, will the character also bypass the very rules they are seeking to uphold?

Better yet, what ties does the character have to that society that can be jeopardized? When the dragon is about to reign fire from the sky, the character is only at risk of death. When the guild is seeking to undermine the character and keep them quiet, does the character have family that can be taken hostage, a house that can be torched, or status that would falter due to a misstep in the past?

Character Definition as Resources

I like to roll on each of those trait tables because is gives me fodder for how to play and present my character. In my most recent game, as a player, there was a GM swap, so we started a new campaign. When I made my character I grabbed Xanathar’s Guide to Everything, turned to p. 61, and ran my character through This Is Your Life, allowing me to flesh them out even more. Why? Because finding out who my character was before they became an adventurer has significant impacts on who they are as an adventurer.

Whenever I am running the game I try to take the character’s backstories into account. The latest game I am running is Daggerheart, which explicitly tells the arbiter to do that, to wrap the character histories into the unfolding narrative. My first endeavor to do that did not go well, but these players are accustomed to 5e, murder-hobo, low- to no-politics style games, so I just tried to get through the blunder as quickly as possible.

Characters should provide fodder to their arbiter that allows the arbiter to include their history into the campaign. I say should very specifically; the game we are playing is about the people at the table, it is about their characters, and so by tying their history into the story it pulls the character, and the player, deeper into the narrative and makes for a much better experience. A fleshed out history gives the arbiter the resources they need in order to best apply this, and characters without any resources will never really be a part of the story.

Medieval As Fantasy

The whole reason I am writing about this is because my latest project, a bit of a doozy, is all about remaking the backgrounds into something, more. The Heartbreaker project has been focused on bringing more of the “medieval” into the “medieval fantasy.” Layered armour because armour was worn in layers. Weapon forms because knowing how to use a sword does not translate to using a polearme. Commerce because the mercantile system was based on silver rather than gold.

The more digging I do into the medieval world the more I realize that “medieval” is as much fantasy, to us, as anything with elves and dragons and wish spells. The societies, cultures, rules and laws, all of these things are alien to most people, including me. Time after time a player around the table will refer to guards as police. Nobles and merchant lords are seen as haughty and self-aggrandizing, rather than as people of influence and power. Lying is seen as something to exercise the skills they chose, rather than a true risk to their reputation and freedom.

Medieval Backgrounds

During some research for generating settlements years ago, I came across a treasure trove of information: a census from Paris in the Middle Ages. I originally thought it was from 1492, but due to my bad habits of keeping my original documents, I cannot remember, nor find them, and everything I have found online points to a 1292 census where a lot of people get this information. Either way, it was amazing.

Originally I was using this information to try and understand how many of the different artisans one could find in a settlement of a given size. Easy, just take the numbers and scale them appropriately for your hamlet, town, or metropolis. But recently, as I have been considering putting serious effort into my Heartbreaker, I came to see this source in the light of my new goals. Over the years my investigation of this hobby has led to a number of different ideas and sources mingling in the subconscious, and I thought that the background system, with this data, could be jumbled up with the idea of a Traveler background, and lately, I had an idea that it could be a “mini-game.”

The Background Mini-Game

Now, this idea is not fully fleshed out, nor is the guaranteed end product, especially since I only thought of it just last night while I was at work.

A lot of the reading I have been doing on substack in the PPRPG community has been about solo games. People have been picking up different games, oracles, and resources to run small campaigns with either one character or a whole troupe. One of the main points I have been hearing is that this is a great way to learn a new system. Just think of it, a game comes out that is similar to many games you know but has a character creation process that is a game unto itself, allowing you to play at your own speed, flesh out a character’s history, and learn the rules by using them, by interacting with them, as you create the character you will eventually take to a group session.

If there is a format for documentation, which does not have to be strenuous, you could summarize your experience into a one- or two-page document that you hand to the arbiter, and have a character with an interesting beginning. What about when my character dies? This is a valid question because I also want Heartbreaker to have a level of lethality that is higher than 5e but lower than, say, Shadowdark, or anything OSR.

Maybe I am the only one, but I think it would still be fun to start playing the little mini-game right there at the table. If there is another hour or two of the session left you could start making your new character there, and although the rest of the players are still in the main game, the social aspect of this hobby will lead to them being an audience for your new story. When you roll that rare or weird thing, the surprise or confusion washing across your face, the other players are going to wonder what happened, and then you can either tell them or not, sharing or building suspense as you choose. It will still be a social experience, and one that I want to discuss more.

Themed Campaigns

This will start as a bit of a tangent, but I assure you we will make it back to the main point.

Some of my favorite games I have even been a participant of were themed campaigns. One of the many GMs around my old table would come to our Saturday all-day session, specifically one where there was a lag in the story or a natural ending point of the current campaign, and they would excitedly tell us all about the great idea they have. If everyone liked it we would build the appropriate characters and be off.

The difference here, is that usually the character options were restricted, sometimes heavily. To many modern gamers this would seem heresy, I cannot even get my players to make characters of different classes, let alone restrict any of their options.

The Overlord

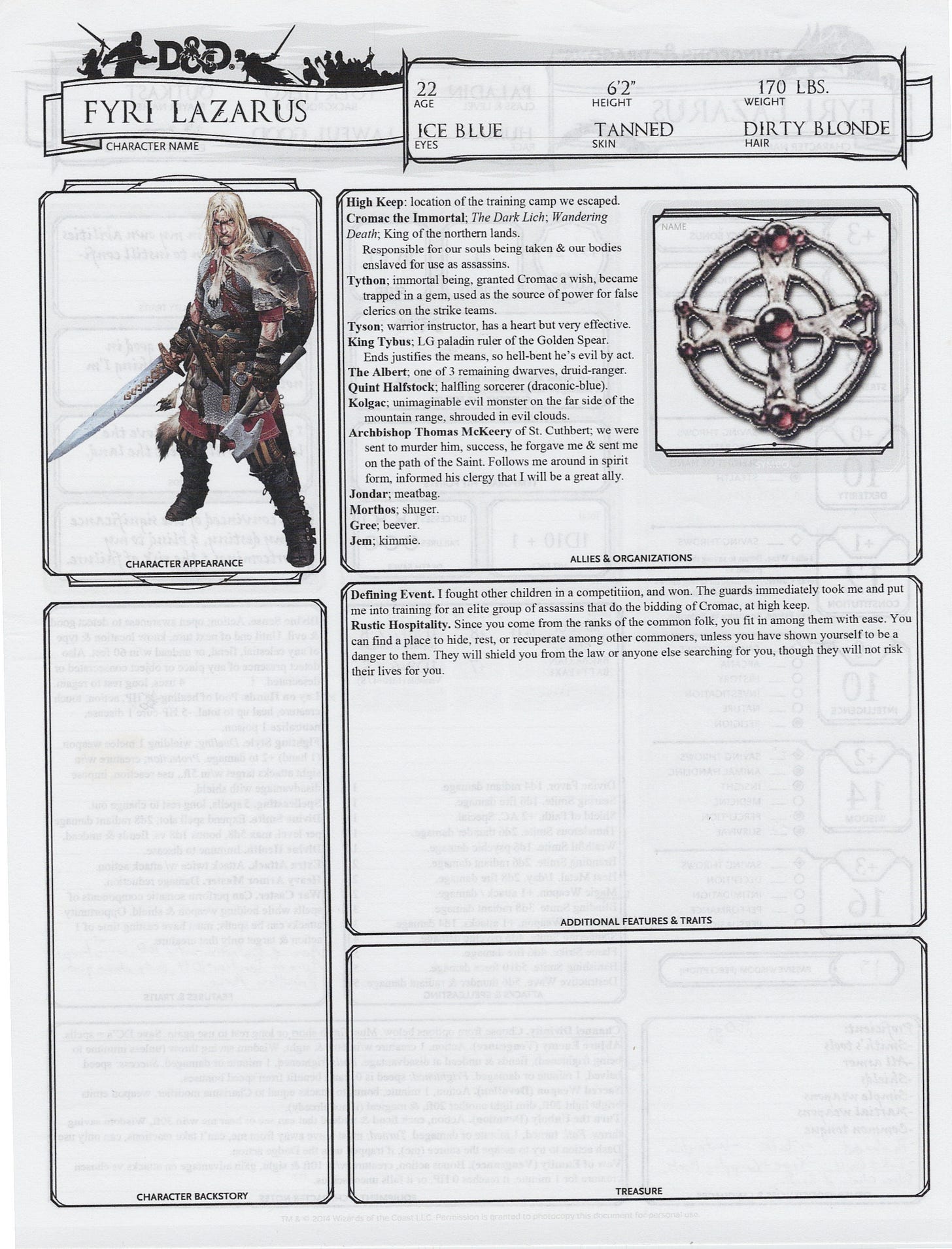

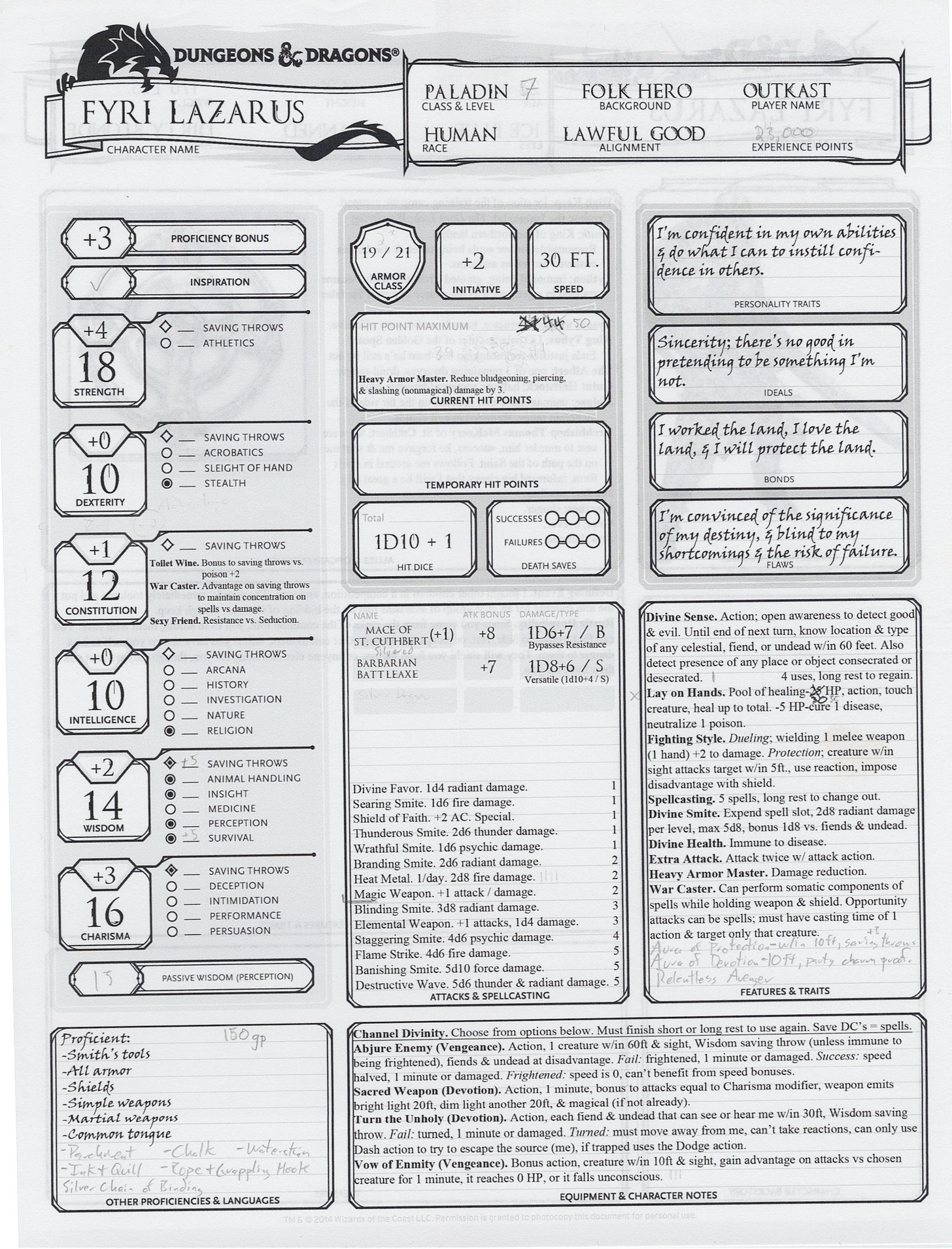

There was never any name for this campaign, so I will name it myself. My friend has this idea that our party would be an elite team of assassins for the evil overlord of the realm. The Overlord and his vizier would travel across the land looking for children with “the spark,” the innate trait that would eventually lead them to the greatness of adventurers. These children were then taken, forced into brutal training camps, and made into the Overlords elite assassins.

The Overlord has a group, essentially a party, of each of his trusted advisors that were the best in their fields who would train each class in their ways before a group would be formed. Each party had a leader, which was my character for this campaign, and we were given tasks. The Overlord’s wizard, we later learned, had stolen a piece of each of our souls, allowing them to resurrect us at the Overlord’s palace should we ever fall in battle. This allowed them to keep us controlled, and ensured that his valuable assets were never truly lost. If we failed an assignment, we usually died, and then we woke up back home. If we succeeded, we could either travel back or intentionally die to save us the trip.

We did not choose where we lived, who we worked for, what compensation, if any, and we did not choose who we were, ultimately. All of that lack of choice led to one of the greatest games ever. I will skip a lot of the details and go straight to the end, because the culmination of this campaign was (chef’s kiss).

Eventually we decided that we were on the wrong side of things and that we needed to get away from the Overlord, find some rebels, and overthrow the evil empire. As we stormed the flying castle, several party members ran off to keep the Overlord and his guardians busy while a few of us went into the hidden basement to uncover the secret to his power. One party member died. The rogue eventually found the hidden trapdoor that led to this secret, and missed the trap but picked the lock, then promptly turned to stone. Two members down.

As I opened the trapdoor, the fight with the Overlord and his guardians got worse, two more party members died. We were almost there, all the death would be worth it if we could undo his secret power. The trapdoor led to a set of stairs, which I quickly followed down, and came to a landing. Another member died, now I alone was left.

The stairs ended in a meadow, by a creak. Below the Overlord’s keep was a pocket of time, one bought from the great Sand Dragon of Time, the moment the Overlord gained the power of a god. When the Overlord was a boy, he lived in a realm that was constantly at war with a neighboring realm. For generations his family had experienced the ravages of warfare, and he wanted to end it.

One day, the boy wandered to a nearby creak, wherein he found a stone. This stone was the god of the natural world, a neutral god that simply lived in the creak and ensured that the world flowed as it should. The boy, upon finding this power, discovered that he could use this power to end the wars, so he took the stone. The moment he came upon this stone is the moment that was frozen at the end of those stairs.

My character was initially a fighter, a tactician trained to utilize every element within his team to their best of their ability to complete a mission. During one of early assignments, the one that started my character down the path of resistance, we were sent to the temple of St. Cuthbert, to assassinate the head priest of the clergy on the prime. There were a set of magical protections that slowly picked off one party member, keeping them from getting into the inner temple, and I was the only one to make it all the way.

The method for this assassination was not a fight, but a delivery. In my hand I held a cloth wrapped around a dagger, and at no time was I ever to touch this dagger with my flesh. My mission was to approach the priest, hand him the dagger, and walk away. As I approached the priest, he looked into my eyes and said, “It’s okay, I forgive you.” Then, he took the dagger. As his hand touched the handle, a dark magic enveloped him like a cloud. His light, the light of his faith, flashed brilliantly as pain and struggle flooded his body and face. Eventually, the battle was won, and the dagger was plunged into his chest, draining the life from his body.

At that moment, a seed was planted in my character. Over time, as we made our plan to escape, we eventually did, and we began to work against the Overlord, my character transitioned from a fighter to a paladin of St. Cuthbert (multi-classing).

So, my character, the last of my party of rebel elite assassins, fighter turned paladin, has come across the moment in time when the Overlord began. I am an adult, veteran warrior, and before me stands this boy, about to be granted a wish by the elemental stone and change the world. My GM turns to me and asks that fateful question, “what do you do?” No one, not a single player at that table, expected to find this, this frozen moment of time, and everyone was leaning over the table with anticipation. So I answered like any experienced player would, “I’m going to step outside and think about this for a minute.”

The chatter and tension was palpable, the whole table was in an uproar at the epic moment we had just come to. This, this is what this hobby is all about. And I thought about it, deeply, and thoroughly, before returning to my seat at the end of the table, across from one of the people I considered family. My friend repeated, “what do you do?” My response was planned, “I approach the boy, and tell him that I can help him to end the strife in his world, that I can teach him to be a ruler worth following.”

The table erupts. The shock and surprise on my GM’s face was overwhelming. He hadn’t really considered what I would do, this was not a planned moment, like any good campaign, he had only set up the situation, but he then told me he didn’t think that that was an option. He figured I would either kill the child, to save the world, or that I would take the power myself to put it in the hands of someone better (LG paladin of St. Cuthbert).

Back to the Ground (background...)

All of that amazing storytelling, all of those invaluable memories, they came from the defining of a character being of utmost priority. What was the background, in rules terms? A soldier? An urchin? Where is the page that defines “child assassin reared by an evil overlord?” There isn’t, which makes me believe that the history of our characters can be more than just a little feature and some tables for guiding roleplay. There is nothing wrong with the existing set, and for a generic “medieval fantasy” rules set, they work great. They have served me for years, well over a decade, but I think they can be more.

By the time my character was in his teens, he was the equivalent of a 3rd level character. My teenager could take on most basic soldiers and city guards and then end their noble or sergeant or important figure before anyone knew what was happening. It doesn’t matter that he may have been overpowered compared to your average starting PC, what matters is that it formed to the fiction and the story being told, and that the mechanics allowed me, as the player, to viscerally feel and experience it.

Level as Measure

Given the hundreds of entries on the census, I have spent quite a bit of time trying to organize them in a way that is useful. One of the primary concerns about larger games with lots and lots of options is “analysis paralysis,” a very real design problem across multiple industries. Anyone that played in 3e and 3.5e knows exactly what I am talking about.

During this process, I at one point started layering the professions, finding those that would be essentially the apprentice-level, the journeyman-level, and then the master-level. I would place these into a small table and give them a level equivalent, 1 for the apprentice and 3 for the master. I didn’t think anything of this at first, I was just trying to figure out how to organize these so that people, including myself, wouldn’t get lost in all the myriad options.

Later, when I came back to it, I saw it as potentially being an actual level, as in character level. This is an interesting idea for several reasons.

What Determines Character Abilities

For the longest time there have been two primary ways to define characters, which have a large influence over the rules set in which they are contained: class and skill. A class ruleset contains a selection of groups of abilities, features, skills, and other defining elements, often fictional, called Classes. These classes are often some sort of warrior, spellcaster, sneak-thief, healer, etc. A skill ruleset contains an extensive list of skills and other abilities that each player can select for their character, allowing a massive range of different characters to be built given that there are no set types or predetermined groupings.

As games have evolved over time, each has influenced the other. In class systems you have subclasses, prestige classes, or simply rules for multiclassing, where you can mix and match the various class sets to your hearts content. Skill systems have predefined sets of skills and abilities that can be selected to allow for newer players to more easily onboard to the system, or for a player who wants a specific experience to just choose a set and move on.

But I think there can be a bit more, and I also think it can be based on the fiction. The idea that a hermit simply wanders around the wilderness for a number of years, doing whatever it is they are doing, and then one day they become a wizard and have spells available to them, is a little too vague. Yes, the player can fill in all these details with an interesting 14-page short story about their history, but I would appreciate a little more guidance. After all, the rules and fiction in the books is provided specifically to guide players and the arbiter in how the game is meant to be played; not as a matter of “this is how you do it CORRECTLY,” more as a point of “this is how we INTENDED the game to be played, this is the experience we wanted you to have.”

So what do we (or I, really) do? We separate certain “class” abilities and put them into the backgrounds. Spellcasting will now be learned in your character’s history, and what you do with it will define what class you have. The weapon forms, skills, and other features will also be gained in your history, and the class you pick is more a representation of how you plan to use those abilities you have gained.

Why Put the Features into the Backgrounds?

I am so glad you asked. Learning how to cast spells is a long process, much like that of school. Yes, your character may have a natural inclination towards casting spells, but the process is complex and dangerous, and most often must be learned as a matter of education. This would happen in the history of the character, not in the present.

Another way to think of this is that a class is how you use the skills and abilities you have, it is your plan for who you will be and what you will be good at doing in the future. A class is a map, akin to a profession, but in these types of games we separate the concepts of professions and classes.

One of the primary ideas I have had for a while now is the battlemage. A battlemage is a fighter; they are a character that focuses on fighting. As opposed to a “normal” fighter, they use the tool of magic, rather than sword and shield, or cloak and bow. When I began to think about classes in this way I could see a great many changes that would allow for more customization, as well as a potentially more accessible and better understood system of magic, even from a mechanical standpoint.

As we all know, because you read all of my articles, and I thank you for it, I think magic can be reformatted, and should be, for the hobby and these games to move forward. If you need a reminder, because it’s been a while since you read that article, here are my thoughts on Deconstructing Magic.

A longstanding issue of D&D in particular is that power gap between high level characters who focus on magic, and those who don’t. Wizards can bend space and time with little consequence while a fighter can hit a lot, and hurt a lot, but would never be able to get near a wizard of “equivalent” level, because they are so vastly different in actual power, as opposed to character power.

Separating magic from the class and treating it like a tool, a dangerous and unstable tool, allows for the reorienting of this imbalance. A fighter is someone who uses their skills and expertise to win violent conflicts. A fighter can use a sword, a polearme, a bow, a spring-trap, or a spell. A battlemage is no different from a fighter, they just use a different weapon.

In this context, a wizard is someone that deserves those low hit dice. A fighter spends their days training to give and take hits. Wizards spend their nights poring over ancient texts, practicing obscure rituals, and experimenting with new components and casting routines. Yes a wizard can ummake reality, but a battlemage can do so with intent; they have trained to lay waste to an entire field of enemies, using spells rather than ballista.

The Farmer & the Noble

The easiest example to use for this class reshaping is the fighter, so we will stick with it. In 5e, a character that was once a farmer who becomes a fighter is no different than someone that was a noble. One is a little poorer and dirtier, but otherwise they are essentially the same kind of fighter. They can both choose to use a sword and shield, ride a horse, and speak to the best tactics their party can use to take on an enemy. In fiction, let alone medieval history, these characters would be wildly different!

Once again, I am using medieval history as a springboard, something more tied to reality as we know it that can be used as a foundation for building complex and believable characters.

Farmers, those who were conscripted and trained to fight in their lords armies, were given that barest of essentials and trained with the most potent weapon of the time; polearmes. Long sticks with pointy ends, sometimes capped in metal and sharpened, and a uniform, occasionally being layered cloth, like gambeson, which provided some protection but more often than not was an identifier so people could tell who needed protecting and who needed the pointy end.

Nobles were trained with the weapons of nobility; swords, shields, armour, and very often mounted combat. Not all nobles were knights, but most knights were nobles. They also had access to more resources, which allowed them to have better armour, and they were given training in leadership, if not tactics specifically.

The farmer was a worker, a laborer, someone who took the land and bent it to their will. Farmers had to work the land, hunt, forage, and engage in mercantile, selling their wares and buying what they needed to perform their duties. As the lowest person on the totem pole, unless there were slaves, they constantly did not get their way, and their lives were expendable to those above them. These experiences build a resilience both physically and mentally, allowing them to withstand the harsh rigors of their difficult lives.

The noble was a leader, trained to manage groups of people that are beholden to their will. They had to learn various studies, most of them hunted, but they required a woodsman or huntsman to lead them through the lands. They did not skin and prepare their prey, they simply took the pride of having felled it. Their life was more luxurious, which gives them an air that people bend to; nobles walk into a place of lessers and are looked to and listened to, not only because this was their societal place, but because they believed it and exuded the atmosphere of leadership.

Now lets look at a new idea, the spellcasting fighter. Most likely this character would begin as an apprentice to some mage or wizard, having been pointed at as a bright lad in their youth or sold to the mage when they needed an assistant. They would spend their life observing and studying, learning to read multiple languages, scripts, and glyphs, poring through tomes at the behest of their master. There would be long nights of ritual casting, trips to gather components and ingredients, with strict guidance for the quality and nature of the products. The standards would be exacting, casting spells is deadly work.

As the apprentice becomes a fighter, they are bending their spellcasting to the purpose of war. Wizards can be many things; scholars, influencers, wardens, but the fighter wants to engage in battle. Like many soldiers of a medieval-inspired setting they could be aiming for high-paying mercenary work, or there could be a leader or cause they believe in. This kind of fighter would never pick up a sword, the tools of a brutish and simple battleground fodder, no they would use the highest, most dangerous, and most elite tool of the arcane.

Wrapping It All Up

The ideas I have covered today are many: backgrounds that are more “medieval,” separating class features from their classes and into the backgrounds, characters that are more defined by fiction than simple groups, and the possibility of a mini-game to introduce a player, and their character, into the game as a group activity.

Will any of this work? Who knows. Will I be able to produce this so we can find out in the near future, especially now that I am starting undergraduate classes, full time, alongside a job to keep a roof over my head and food in my belly? Doubtful, but only in the sense of timeliness.

What I can say is that the work on the iteration of backgrounds continues, and I am currently still organizing them, which is allowing me to get a full grasp of the scope. I have some ideas on how I want to start categorizing them, that way they can be more accessible to players (and myself), which is also leading to some thoughts on how the mini-game would work. In the medieval world children did not go to school, they worked. If their family were peasants, they worked the land and assisted in all sorts of tasks around a farm. If their parents were artisans, they learned the family trade so they could continue it once their parents retired (either being too old to continue working or they passed). Some children who were seen as bright could be sent to monasteries and become monks. Noble children were given education in many forms, both scholastic and martial in nature. But, all of them did something, and that something defined who they would become.

Right now I am thinking character creation begins with learning who the family is: artisan, peasant, nobility, merchant, etc. From there the different professions will be defined in larger and larger groups, allowing the player to discover their character’s history through expanding tables and options, though curtailed so as to avoid analysis paralysis. I prefer rolling to determine who your character is, I think the experience makes for a much more interesting character for both the player and everyone else at the table. Every time someone brings an “optimized” build to the table I yawn as they play out the same tropes and do nothing original or interesting, even in combat, where they are supposed to shine but just end up being as boring as if they were a video game NPC.

Thanks for reading.

And if you want to help me in my quest for knowledge, scratch my itch (get it?!).

Great article. Loved it. I think the idea of a traveler like mini game to create characters is genius. I have played and referred several traveler games and would be happy to answer any questions you have about that.

Great article as always!!